In the post-modern era, it’s hard to find a pair of artists more different than Mariko Mori and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The former, a Japanese real estate heiress turned model, dealt primarily in photography, digital art, and some sculpture in her work from the late 1990s to the early 2000s — works that evoke a dreamlike, almost hyper-real aesthetic. The latter, a trilingual child of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, worked in a style derived from his earlier street art, crayons and paints in harsh, jarring styles.

However, both Mori and Basquiat — despite creating works informed by nearly opposite experiences — seem to tap into a common vein: a tinge of artificiality perceived in world around them, possibly relating to a feeling of disconnect. While this theme is common to the two of them, the imagery (like their backgrounds) could not be more different.

Birth of a Star – Mariko Mori – 1995 – photograph / digital

Most of Mori’s early photography work features herself as a model, almost exclusively in-costume as a character of her own design. In Birth of a Star, she lampoons a Japanese television program of the same name, turning herself into an artificial pop artist.

Of particular note in this image are her hair (reminiscent of the popular “Troll” figurines,” her eyes, and the mechanical-looking outlines on her knees. The result is alien, almost unsettling, especially when observed for a longer period of time.

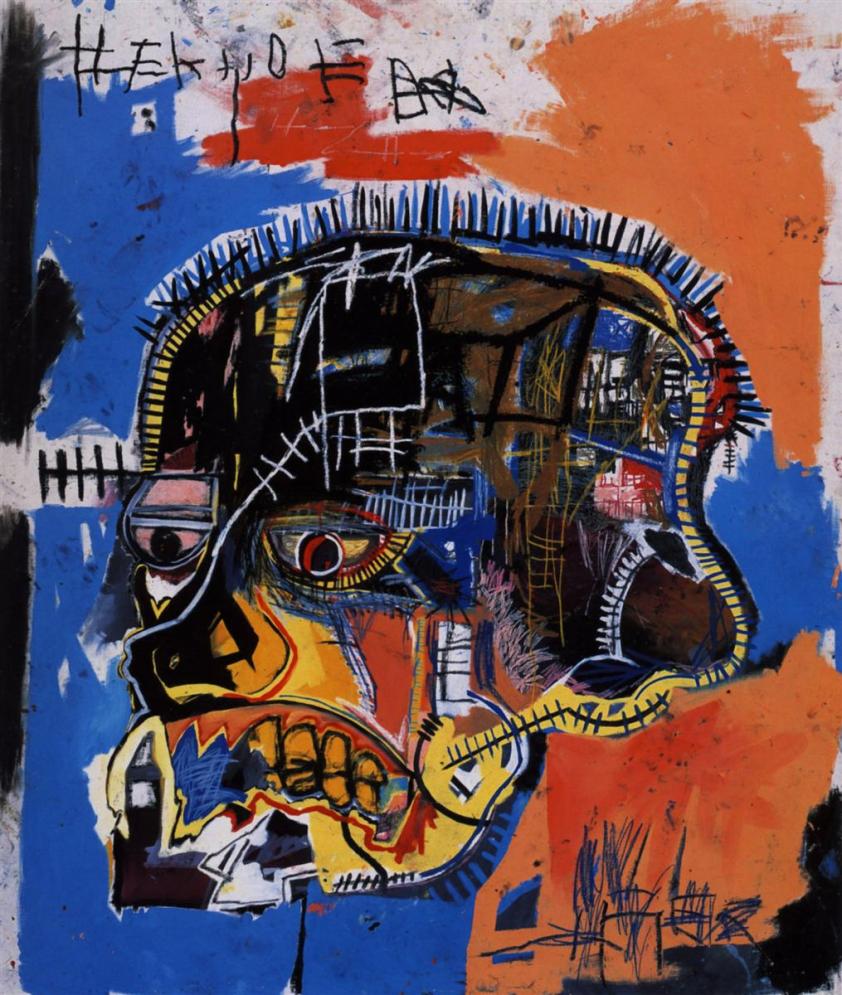

Philistines – Jean-Michel Basquiat – 1982 – acrylic / crayon on canvas

Though some observers may consider Basquiat’s style to be unsophisticated, perhaps even childish, I could not disagree more. Though they share much in common with street art (which is often relatively simplistic), the attention to detail in his works is astonishing and deliberate. I personally find them to be jarring and challenging — though not unpleasant to view.

While Basquiat was inspired in part by a copy of Gray’s Anatomy (given to him during a hospital stay following a childhood accident), his use of straight lines is relevant to our discussion here. The forms in Philistines take on an almost mechanical quality, with the mouths of the subjects appearing to be grates, their heads and chests appearing to have rivets. The figures could almost be taken as fake people, automatons spawned by the cultural norms Basquiat sought to protest.

Empty Dream – Mariko Mori – 1995 – photograph / digital

Mori appears as a mermaid four times in this image, another of her surreal characters which seems to be retain the mythical role of its source material. In addition, the setting (an indoor beach) adds a further skew from reality — resulting in a scene depicting a magical creature in an artificial place. We’re left not sure if Empty Dream is reality, a virtual construct, or something else entirely.

Untitled (Fallen Angel) – Jean-Michel Basquiat – 1981 – acrylic / crayon on canvas

In corrupting the classic Judaeo-Christian imagery of angelic beings, Basquiat seems to call into question beliefs that are considered typical in our society at large. Artificiality makes an appearance here as well — the angel’s eyes evoke lenses, while the halo could almost be seen as a fluorescent light. The choice of bright, bold colors in a limited palate reinforces a feeling of a being that is beyond the real, despite being a product of it.

Sky Temple – Mariko Mori – 1995 – sculpture / digital

The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once stated that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (often referred to as “Clarke’s Third Law”). One of Mori’s first works outside the realm of photography, Sky Temple is part multimedia installation, part sculpture, and fits Clarke’s Third Law to a tee. Though it clearly mimics the style and form of a Buddhist or Shinto temple, the use of glass and lighting conveys the structure beyond reality. This hyper-real feeling leaves us guessing, yet again, if the structure is mythical, or simply technological.

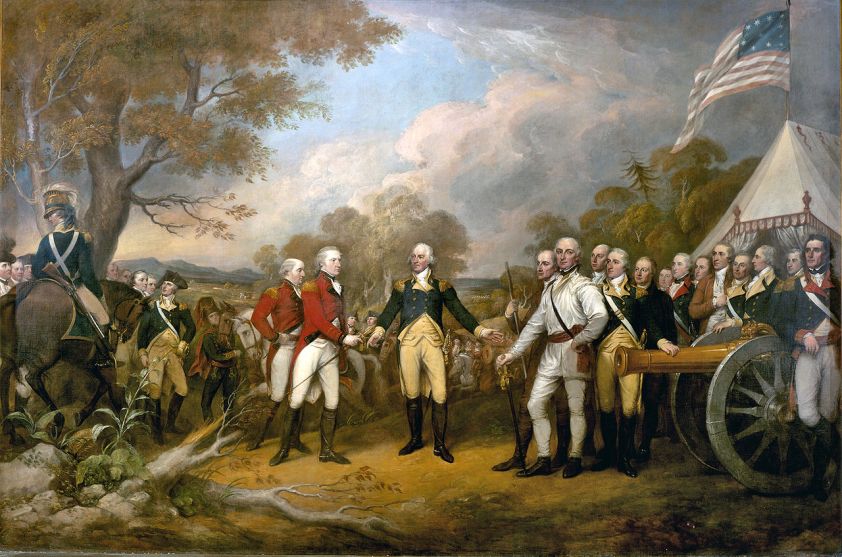

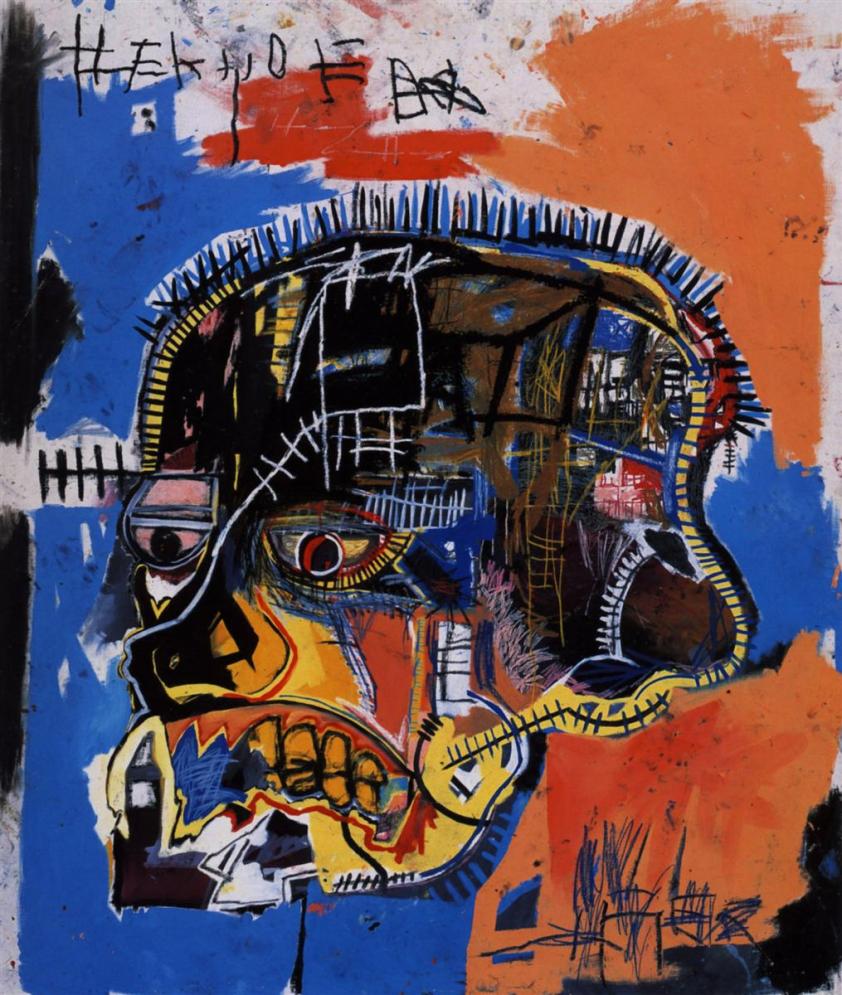

Scull – Jean-Michel Basquiat – 1982 – acrylic / crayon on canvas

With its exposed scaffolding and lines that resemble railroad lines, Basquiat’s Scull manages to seem metallic despite its use of strong primary colors. Though it may be a little surreal-sounding, I’d argue that we’ve all felt like Scull looks at some point or another in our lives — struggling with our emotions and stresses, despite the barriers we erect within as demanded by our society and culture.

“The Artist.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 July 2015. http://www.basquiat.com/artist.htm

Itoi, Kay. “Tea with Mariko.” Artnet.com. N.p., 20 Nov. 2001. Web. 28 July 2015. http://www.artnet.com/Magazine/FEATURES/itoi/itoi11-20-01.asp

“Mariko Mori.” Sean Kelly Gallery. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 July 2015. http://www.skny.com/artists/mariko-mori/

Brown, Emma, and Henry Geldzahler. “New Again: Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Interview Magazine. N.p., Jan. 1983. Web. 28 July 2015. http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/new-again-jean-michel-basquiat-/#_